On May 1st, Richard Guest & I visited Mark Wallinger’s show ID at Hauser & Wirth London W1. Afterwards, we discussed the show by email. The following is the result of several weeks’ electronic toing and froing. You can read part Two here:

…David: In the way you describe it, Ego comes across as a possibly disingenuous but certainly disarming glimpse behind the scenes at the moment of artistic creation in 2016. I like to think the ink under his fingernails is from the Id paintings, and Ego represents a kind of dumb show which shows the conscious perception of the creative moment in the mind of the artist in all its glory and shoddiness. Maybe it started as a sarcastic gesture of either satisfaction or dissatisfaction. I can see that it is in a way describing the meeting of our modern selves and our cultural past, but can it simultaneously subvert and promote the creative act? Wallinger seems to be saying this is nothing, but is also everything…can we absorb that paradox?

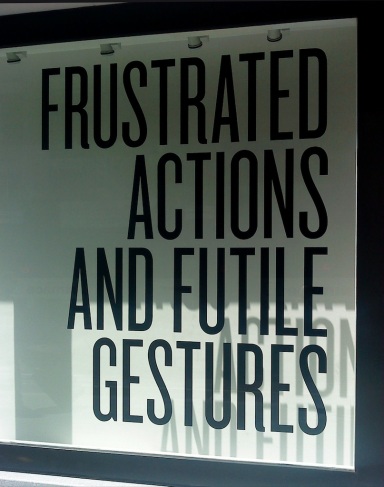

The Id paintings seem like a cathartic release of the need to paint, to make marks and of course the need to make big canvasses to fill that huge space. Can’t do that with a couple of sheets of A4. They are giant Rorschach tests, no more, no less. On the one hand they seem to be a weak echo of Yves Klein’s Body paintings , on the other because they are so many and they are all the-same-but-different they seem to be devaluing and denigrating the gestural mark in art. Wallinger seems to be saying ‘marks are nice to look at and fun to make, but in the end one mark or the other – take your pick – call it a face or a cloud if you like – but it makes no odds. All that remains are just the marks. Everything else is your interpretation, based on the primitive parts of your brain that needed to make sense of abstract shapes when we were hunting in the wild and painting in caves. Sort of Anti-Impressionism. Anti-transcendence. We are not in the wild any more.

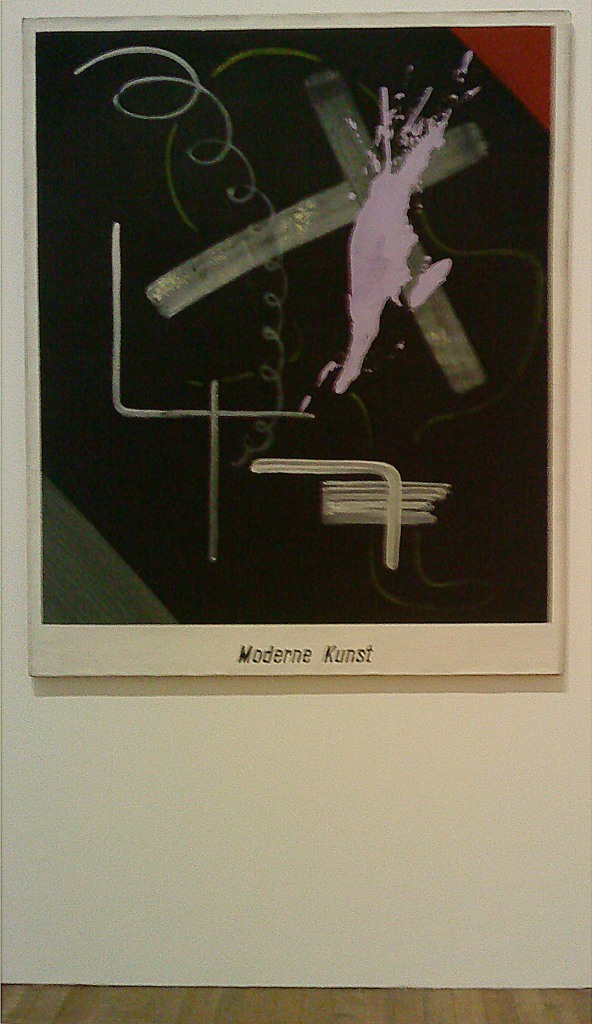

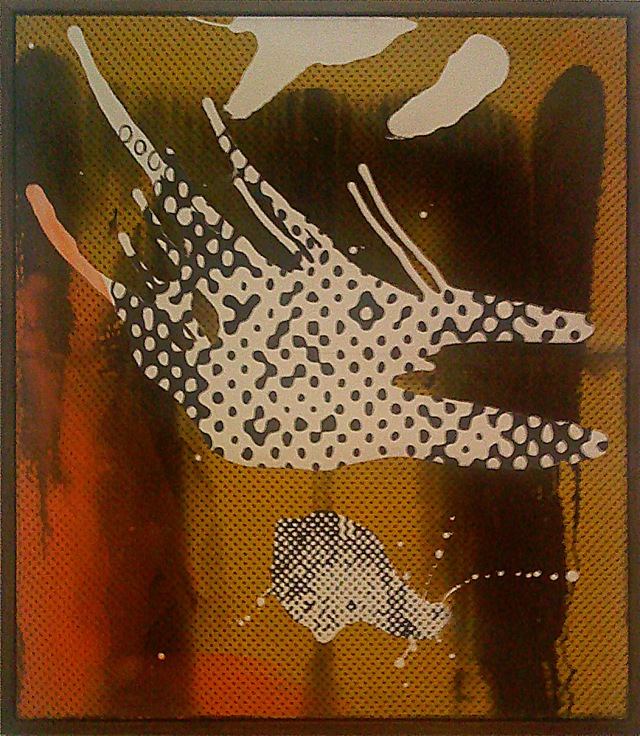

Mark Wallinger ID Painting 29 2015 Acrylic on canvas 360 x 180 cm / 141 3/4 x 70 7/8 in Photo: Alex Delfanne

Richard: I’m not so sure…maybe this is a tentative (not so?) step in that direction. One definition of the Id is: the part of the mind in which innate instinctive impulses and primary processes are manifest. Are these paintings titled Id because Wallinger followed his instinct to make marks with his own hands, rather than develop another clean, cool, detached neo-conceptual work? Or has he found a conceptually acceptable excuse to be a painter again (I’m interested in their conception. The canvases are divided vertically down the middle, so that the two sides of the painting roughly mirror each other. There are variations in some marks, which underlines the hand-made quality. But in some of the paintings there are clear central dividing lines, like the ones you get if you try to create a mirror image in image manipulation software (such as Photoshop) (very difficult to get rid of, believe me…) Which makes me wonder whether MW created his images digitally and then used them as a model for the eventual paintings).

They look like they were a lot of fun to make (and I’m disturbed that so many of them suggest to me scenes from Star Trek). And I’d hazard MW was a lot more physically involved (he, not a studio assistant, made these – they are effectively massive finger paintings) in the creation of the final objects than he was with Ego and Superego, so there’s a lot more of him present in the Id works.

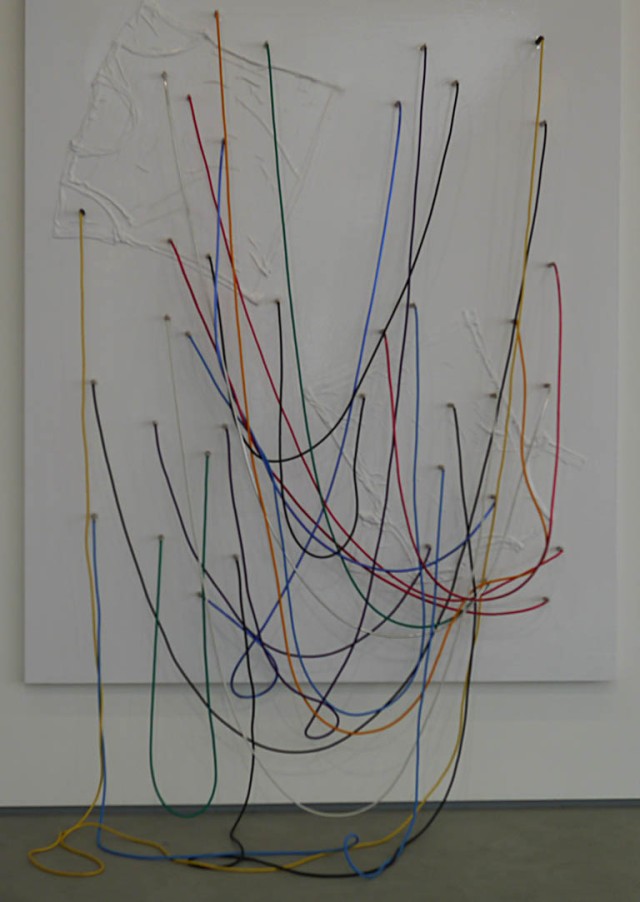

Proportionally, the paintings take up a lot of space at Hauser & Wirth. If this show is about the act of creation, which I think it is, does this mean Wallinger is placing more value on the Id than the Ego and Superego in the creative act? Do you think the paintings have more worth as works (and consequently monetary value)?

Mark Wallinger id Painting 56 2015 Acrylic on canvas 360 x 180 cm / 141 3/4 x 70 7/8 in Photo: Alex Delfanne

David: It clearly is no accident that the paintings are linked to the primitive part of the brain, and photographs and printing are linked to the conscious. Photographs capture an image of something that already exists. The moment of the shutter opens is the moment of cognisance: analogous to the awakening of consciousness of the ego as it observes the world and perceives its own distance from it. Paintings – particularly abstract expressionist paintings like the kind the id paintings reference – seek to be making visible the viscera of the internal subconscious without reference to external reality. The Id paintings feel like therapy, but their context points to an ironical rather than a straight reading of them. Freud was a long time ago and any reference to him feels retro, knowing – like wearing a tweed jacket and smoking a pipe.

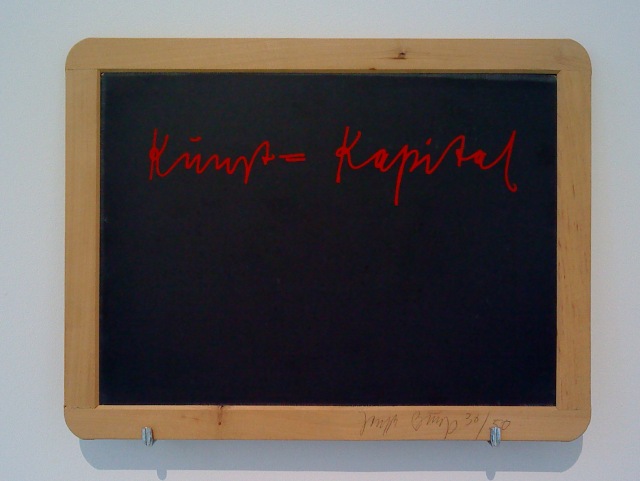

To me it is like this. Wallinger feels (deep down in the unconscious part of his brain) the need to make art. He gets a three metre canvas (well, he gets quite a few of them because after all he has a big show coming up) and starts to finger paint black on white in a sort of planned-unplanned way. It feels honest and direct; but Wallinger is reflective and oblique. Maybe he did do a digital version first. But I think the tactile element is important here. Having made a couple of id paintings he sits back with a coffee and a cigarette (reaching a bit here). In this contemplative moment of self-awareness he sees himself clearly. He is a creator of work, yes. But the work is unsatisfactory, tawdry, second-hand. And unbidden the image of the Sistine Chapel comes to mind. He compares himself to Michelangelo…maybe arrogantly, maybe abjectly. He touches his own fingers together in a sardonic act. Both acknowledging and taking the piss out of his own self, his work and his situation as a leading contemporary artist. He is in that moment God, Adam and Wallinger. Then another level of mind above all that kicks and and says “hey, you know what? That might be a work there you know?” Ego is born. It is rather a feeble specimen next to the lusty Id paintings and the cold, blank Superego and I wonder who might have the courage to buy it ahead of the other larger archivally made gallery fillers…