Pierre Huyghe Uumwelt (From the Serpentine Gallery Guide)

After a fairly long break Richard Guest and I visited two shows – Pierre Huyghe: UUmwelt at the Serpentine Gallery and Walter De Maria: Idea to Action to Object, at Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill. This is the resulting email conversation, in two parts. You can read part I here

Richard:

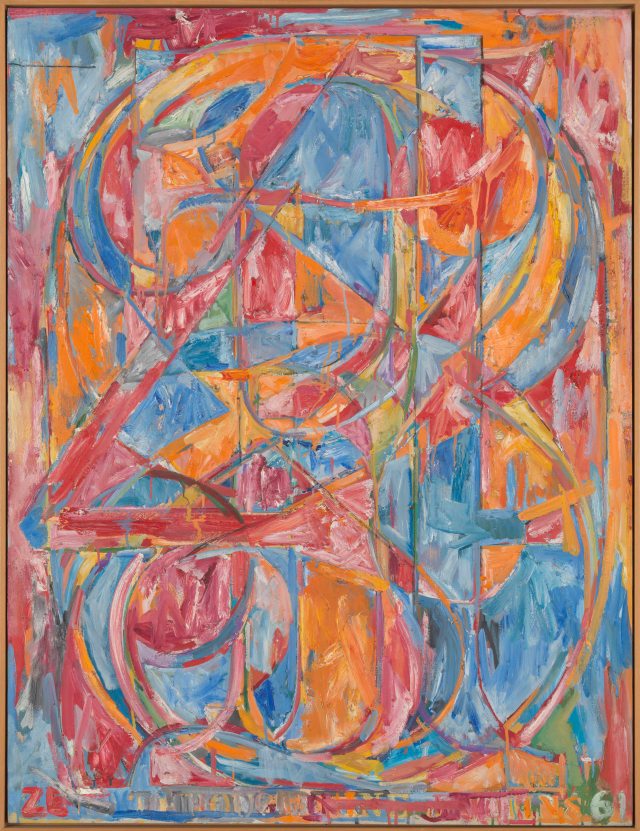

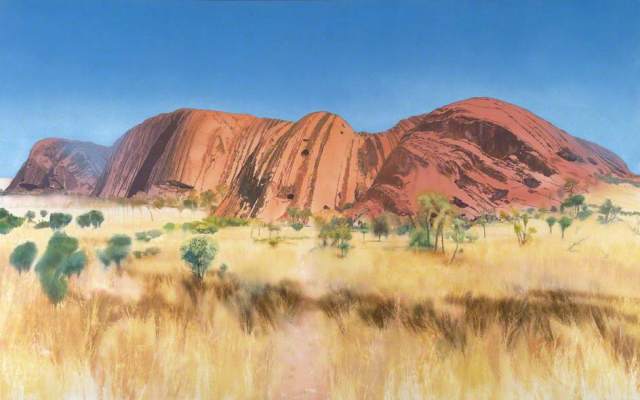

Making a simple comparison between the two exhibitions, Huyghe is ceding his creativity to a machine, with the expected in/ un-human result, whereas de Maria’s work is not only driven by utopian ideas, but is all on a human scale – there are balls to pick up and drop, human interaction is imaginable (and encouraged in his drawings) and looks like it would have a satisfying tactility.

I’d like to see more work by Huyghe to get a better sense of where he’s coming from – is it all at this vast remove? The larger de Maria works seem consistent with the works in this show – Lightning Field and Earth Room still work on a human scale, are understandable as concepts and a person could interact with them.

I think conceptual art has changed a lot in its intentions over time: ideas are being expressed for different reasons now than they were in the 1960s and 1970s. It’s quite an enduring form in a way, but is Huyghe an artistic descendant of de Maria?

David:

Interesting that you say Conceptual Art is an enduring form – since it was originally fundamentally opposed to form – it suggests that it has defeated itself or been consumed by the market. I am not sure that’s really a fair analysis though.

The Dadaists were the first to sever the link between the Object and the Idea. They were the first Conceptualists. But now that has spawned so many subgenres: some are just ideas without objects and some are objects without ideas. ‘A concept in search of an idea’, as we used to say! The difference would be that some of these empty object based artists now describe themselves as Conceptualists: although their work is as decorative and devoid of meaning as any flower painting or animal sculpture.

But there was something right about the overall plan of Dada – it was partly a reaction to photography and mechanisation that threatened to democratise art to the point where skill based reproduction of the visible world was immediately obsolete. Today that process has all but overwhelmed the creative impulse as we are swamped with everyone’s ‘creative’ images, but that is not all. I would argue that the pervasive framework of the internet has made it almost impossible to have an original idea, or even to believe that you have had one. This has led to artists like Huyghe, who are trying to think their way back to the possibility of an idea emerging in the brain unprompted by the collective consciousness. That is what this work was about and – although it wasn’t completely successful for me – it did have a mind’s eye kind of quality to it as if you were witnessing a visual idea take shape. That’s pretty amazing and yes, quite original.

De Maria seems to have had no such difficulty in owning ideas and feeling that they were original and exciting (even though some of them might not have been). So, in answer to your question, although they are both related to the roots of Conceptualism they are from very different branches. But I could be completely wrong! I am not sure if either of them are as in earnest as they seem at first glance. In particular, I feel I don’t totally fathom de Maria’s humour – how do you perceive that, especially in relation to some of the very dry looking sculptures he came out with..?

Walter de Maria at the Gagosian

Richard:

I’m not sure it’s humour so much as light-heartedness. There’s a generosity of spirit behind the drawings, and a sense of inclusiveness to the sculptures. There’s also no mystification to the process: Walter makes a drawing setting out what he intends to do (annotated in plain language), and executes the sculpture according to the drawing – there’s seemingly no barrier/ framing device between him and the viewer. (Hi, I’m Walter, this is my idea, hope you like it!) It’s all of a piece with his Utopian intentions I think. I appreciate what you’re saying about Huyghe and his originality and I agree, but the work is troubling and alien and (without any kind of background reading), opaque. To what extent do you think it’s important that exhibitions are supported by texts? With both of these shows I went in with very little prior knowledge and trusted my reactions to the work without the gallery’s framing context.

David:

This is a question we always come back to. I want to feel that anyone can interact directly with art without background information from the priesthood of critics and gallerists, without other peoples’ interposing opinions or even the artist’s own backstory of the work. I want art that has the power of creation within it, not some weak commentary or reflection flaking off our society like a dry scab.

However, this also means that as a viewer I have to be in a pure state of mind and heart, unclouded by irrelevant thoughts. And the gallery itself would have to be some perfect bubble of contemplation. This is only partly possible…when art works, it is like a radio broadcasting the artist’s mind, and all this other stuff is like static around that signal. But to feel meaning in it, art cannot be wholly disconnected: it has to strike a resonance with my life and experience. Without that – it’s just junk.

On the one hand it is really exciting to have that connection with an artist whose life is remote to mine, but it is necessarily harder to establish that connection and what can be communicated is less detailed and specific. Probably it is restricted to what used to be called The Human Condition, although you don’t really hear that phrase much anymore. All ephemeral or topical content quickly becomes lost.

Art criticism is a kind of oral history that no-one is curating. Its development will be lost – and that is probably a good thing; but we will find the art of the recent past to be almost inexplicable when it is primarily oriented to that critical debate. And if I’m honest I see both de Maria and Huyghe in that camp.

★