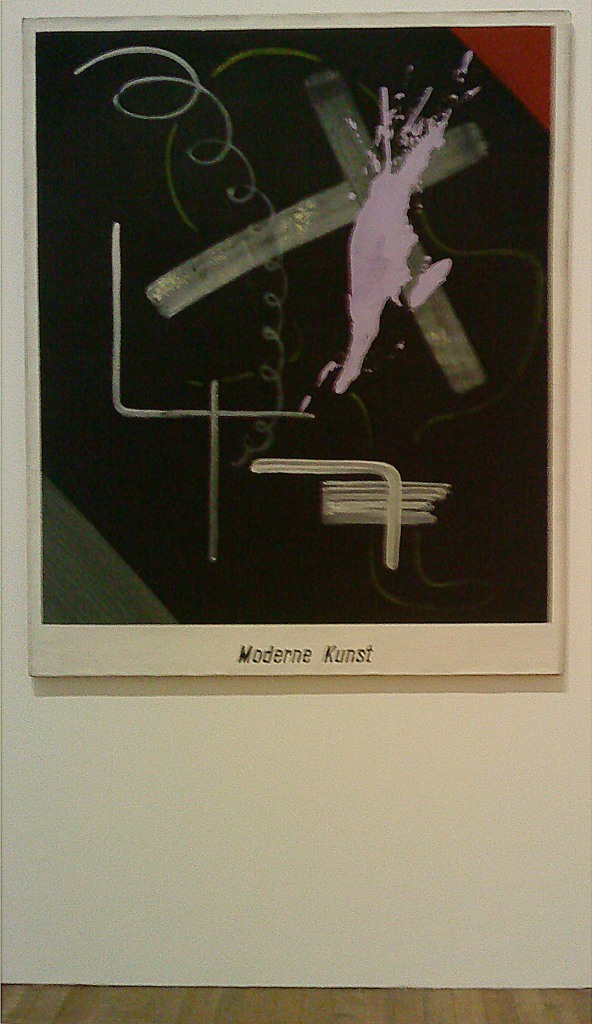

Sigmar Polke at Tate Modern

Polke is the most enigmatic character in all of contemporary art. His work inhabits a phantom dimension between art and anti-art. A sort of artistic wormhole which distorts the usual values and perceptions, and in which a lesser talent would be crushed to nothing.

For many years I have wrestled with Polke’s work, seeing it and not seeing it at the same time. I just could not understand h0w any painting (and I am just interested in his paintings really) could be so beautiful and so ugly at once as his are. I don’t really know whether I like them or not and I am not sure that it matters. I think ultimately Polke only cared about stimulating a certain response in his viewers, which was a complex compound of dissatisfaction, questioning, aesthetic awareness and a kind of transcendental indifference to everything.

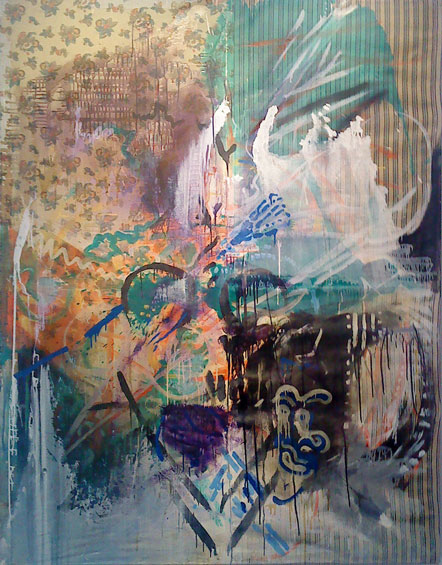

Like all good artists though, he didn’t care to repeat himself and his work takes many forms, and given his rejection of fixed points of reference it is hard to perceive the core, but it may well turn out that the core is rejection. Obviously if you reject everything all at once you won’t make anything, but he seems to have started with rejection of the Nazi past that was so recent for him (he was born in Poland in 1941), but followed that by rejection of post-war consumerism in the early 1960s, and by the time that he was rejecting perceptual reality in the 1970s through his drug use he had also embraced many rejections of new and traditional artistic styles in an exhausting contrarian Odyssey, and for the rest of his life (he died in 2010) he did not slow down or resolve into any obvious pattern, but he often backtracked and took on things he had previously rejected.

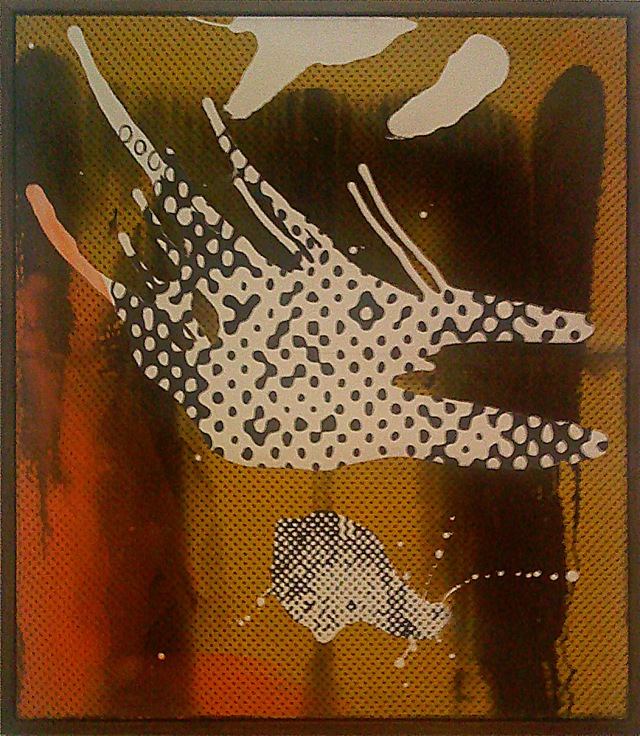

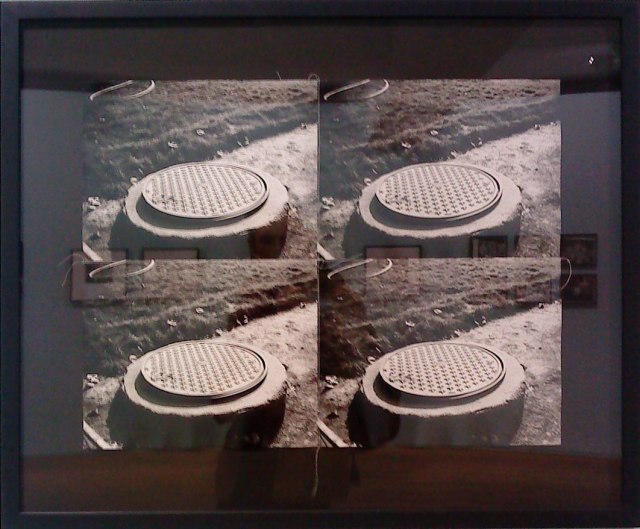

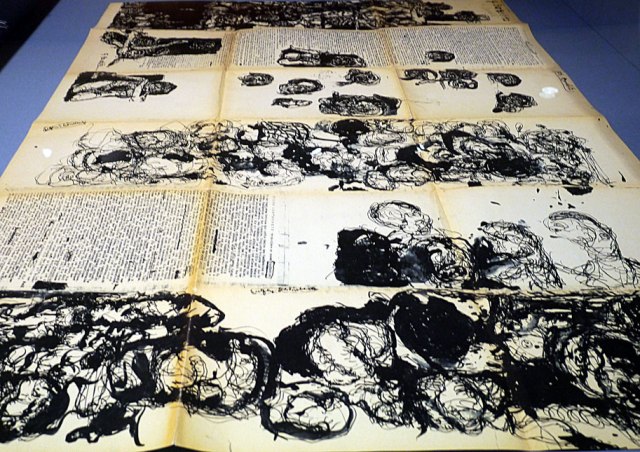

Disintegration of patterns was for Polke suggestive of the disintegration of meaning – of photographs, of images in general. His use of fragmented images anticipates layers of computer graphics but also shows that using images in this way will hasten the descent into the void. To subvert the power and meaning of the images you are using even while relying on them for that very same power and meaning: he knew years before us all that photography was dead as documentation, and showed it reduced to entropic pattern.

He used a hundred different ways of making transparency and translucency on the canvas in order to make his work more opaque.

I don’t go to Tate Modern that often, about once a year I reckon. I am not sure about it I feel obscurely oppressed by its omniscient orthodoxy. This time I went in the evening, and it was the best it has ever been. If you are going to try to give some mental space to art, you need some physical space to do so. It was just us and a few glamorous Italians who were really very decorative.

Polke’s use of spillages and other accidental marks seems an echo of Pollock, but his use of ‘ready-made’ images and printed fabrics seems an echo of Duchamp. Between art and anti-art lives the wizard, and like trying to identify the location of a mythical place, clues are often misleading. For many years he claimed his work was dictated by ‘Higher Beings’. Was he joking? Polke has made an enchanted world without certainties, where everything is open to question. That is not an easy place to live, but it is a free one, and I will return.