During the first phase of Lockdown Richard Guest and I made a few virtual gallery visits – here is our equally virtual conversation that followed…

David Locked down and desperate for art – the art world’s response to the emptying of galleries has been to try to tempt us to a new gallery experience online. we have decided to visit three ‘online viewing rooms’ to try to get our art fix:

The Frieze New York Viewing Room

https://frieze.com/fairs/frieze-viewing-room

Rodney Graham at the Lisson Gallery:

https://www.lissongallery.com/online-exhibitions/rodney-graham-painting-problems

Hauser & Wirth Menorca in VR

https://www.vip-hauserwirth.com/hauser-wirth-menorca-in-vr/

I managed to visit all three sites, but I’m not really sure what I saw. It looked like art, but it didn’t feel like art. It was really very odd. It was a very different kind of art experience: on one hand, it was just like visiting any website, but on the other there was a certain self-conscious quality to the presentation of the work that gave me quite a lot of insight into how and why I enjoy looking at art at all. How did you get on?

Richard: Yes, I’ve visited all three and plan to return to them during the course of our chat. The differences in the galleries’ approaches are interesting. Not sure how much the different experiences are going to colour my reaction to the works.

Frieze is the most like an online shopping experience I think (including price tags), so the layout is clean and you get a nice big picture of each object on sale in the various galleries represented, but it’s pretty static.

The Lisson kicks off with a jaunt round the exhibition space in the form of a short video and follows it with the rest of the page taken up with pictures and descriptions of Rodney Graham’s works.

Hauser & Wirth’s tour of their new gallery in Menorca is the most ambitious of the three, using VR and game technology to simulate the experience of visiting a physical exhibition. It’s very easy to access, silent and begins outside, so you get to walk through the gallery doors. There are various marks to guide you to different viewing areas and other marks to access information about each work. The downside is that the image naturally warps as you move around, presumably because of the kind of camera used to shoot the show.

Of the three presentations, I like the Lisson Gallery the most – the film sketched out the layout of the show and the isolated images of the works filled in the gaps. The Hauser & Wirth is fun, but slightly frustrating – as in shoot-em-ups I want to be able to wander off the prescribed map and have a nosey around in the areas we don’t have access to.

Looking at these showed me how much I miss being in a physical space with objects and other people. When I visit a show it’s a little like stepping out of everyday reality for a while. When you’re accessing an exhibition online, you’re still rooted in your reality (your office, bedroom etc) – there’s no sense of occasion. I find it grabs my attention less maybe because it has to fight with other distractions.

David

Clearly online viewing is no substitute for a real experience, it is more like a menu than a meal. I am a bit surprised at how inadequate it is. The differences are instructive as they tell me what I like about the whole gallery experience. I felt no emotional involvement in what I was looking at; there was little focus or intensity, and there were a lot of peripheral noises from the internet and from being at home. I was missing material detail, scale, true colour not to mention the charismatic presence of the art object.

The time things take to load is also an issue for me. I’m very impatient and want to look at everything all at once, but this is like traipsing round a very crowded exhibition in some kind of Soviet style queue. Not liberating at all.

I hate the cameras of the vr – so wide angle – distorted as you say, and very gamy.

The filtering of an experience through many layers of media is something we are so used to it passses almost unnoticed a lot of the time, but online gallery viewing is very self conscious and it gives us insight into the essence of contemporary art. I also felt the Lisson offering was strongest. But it begs the question: does the online viewing suit some work more than others?

Richard:

While we’re on the subject of substitutes for the real gallery experience I realised the other day that reading a monograph, an art magazine or a history of art is a more satisfying experience for me than trying to look at shows online. There is at least a little more tactility viewing art on the page (and fewer distortions in reproductions)…the only drawback is that you can’t view much new work this way (although, and I don’t know whether you are finding this during lockdown, I’m more interested in rediscovering old stuff in both art and music)…Anyway…online viewing…I guess it maybe works better for digital and video works, although scale is naturally dictated by the size of the screen you view them on (which in the case of Douglas Gordon for example would change the meaning of the piece because the screens used in gallery shows create a kind of installation, and you are missing the hum of projectors, the smell of the room etc) and you still have the problem of distraction as you say.

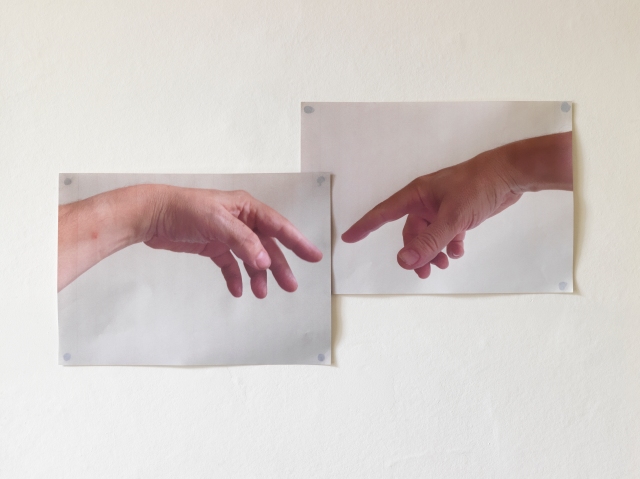

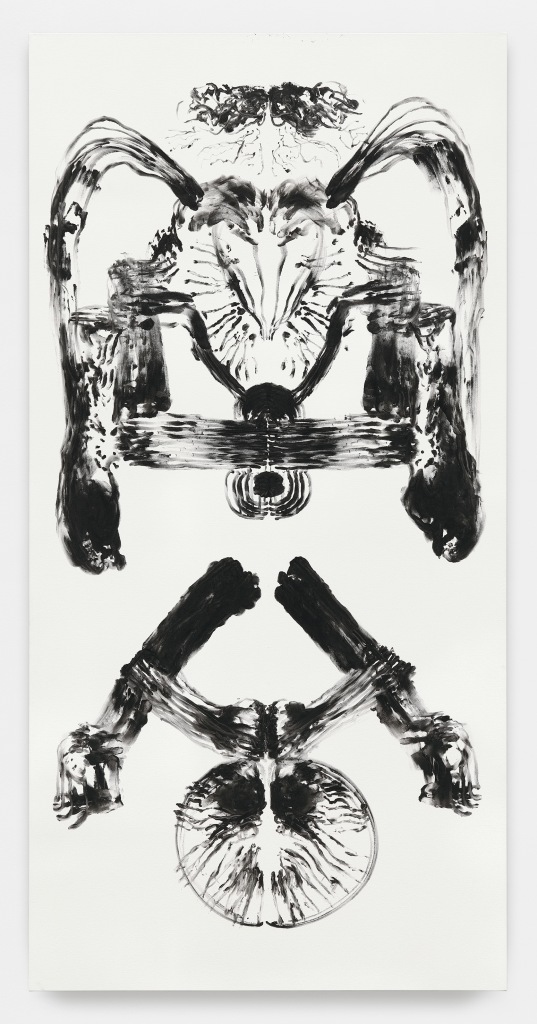

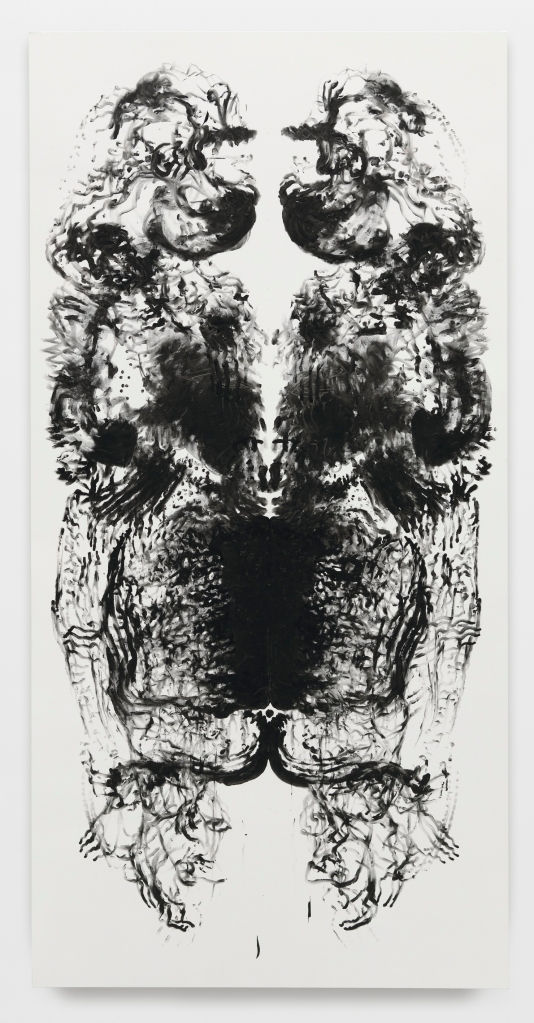

The three examples we’re looking at are broadly similar types of work – 2D paintings, drawings etc and looking at them again I’m struck by how much more I prefer the Lisson approach – I’m happier to spend more time looking at the work even though I don’t necessarily prefer the work to those in the H&W show – I’d like to get a closer look at the Paul McArthy painting for example.

I’m beginning to feel the online exhibition experience is closer to leafing through a slightly unsatisfying exhibition catalogue than anything else and the economics of the situation are less well hidden than they usually are – the physical art would usually act as a much bigger distraction from the obvious shopfront.

Do you want to talk about any of the individual works – I’ve just received an email about what sold at Frieze…

David

I found the filtering options on the Frieze site an odd way to categorise art. I can tell you though that there were no works by a transgender artist for $1m+.

There were interesting works on the site, including this Robert Motherwell picture,

but really we are just guessing what the real work is like – the scale, the texture of the unprimed cotton duck and of course the colour. One thing that I do know is that colour representation on screens is very variable. Overall, the Frieze site fulfilled my worst expectations of the online art experience. However, there are great online art experiences out there – I was blown away yesterday by this site: http://boschproject.org/#/book/

It allows you to get much closer to the works than you ever could in a museum setting, enabling a unique and intimate connection to the paintings. But they aren’t trying to sell you anything. What did sell?

Part Two here